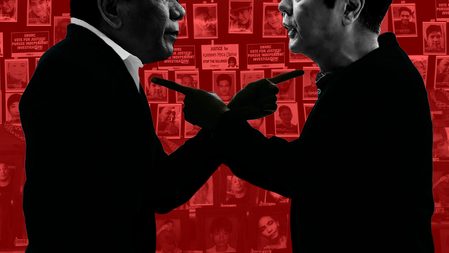

Stories of indiscriminate and willful brutalities in Rodrigo Duterte’s war on drugs gain increasing credence as more informants come forward to testify at hearings in Congress now that he has been out of the presidency for more than two years.

These stories are not just affirmed but enriched with fresh details in testimonies by self-confessed participants in the plotting and prosecution of that war, which left thousands dead, mostly small fry like drug retailers, passers, and users. And the most remarkable of those testimonies so far have come from a longtime close Duterte lieutenant who has confessed being in on the plot — and Congress is not even done with her.

Royina Garma served with the police in Davao City when Duterte was mayor there. Upon her retirement, in 2019, on the third year of Duterte’s presidency, he appointed her general manager of the Philippine Charity Sweepstakes Office. She testified that, even before Duterte was installed president, she had picked for him, as he had asked, the man who organized the task force that prosecuted his nationwide war on drugs. That war, she said, had been modeled, down to its reward system, upon the war for Davao, only upscaled. She proceeded to name names and match them to roles in the war. For instance, Bong Go, by all accounts the closest Duterte trustee, now a senator, was named as the bagman.

It’s not as if these stories had not been told before or told credibly enough, although Garma definitely had something to add to them, not only in details but also in weight, by virtue of her place in the scheme of things. In fact, the first revelations, coming out early in Duterte’s presidency, had been from two confessed assassins for him. That’s why, since implicating him, Arturo Lascañas and Edgar Matobato had to be kept hidden, out of reach by Duterte.

What the SC says

Even now that the coast may have become clearer, they have not resurfaced. Matobato, who has confessed to around 50 kills, has been moved from sanctuary to sanctuary by his church and civil-society protectors. As for Lascañas, a police officer and confessed linchpin on Duterte’s Davao Death Squad, so called, he needed to be spirited out of the country. His next stop may well be The Hague, as a witness against Duterte at the International Criminal Court.

Duterte and his police chief in Davao and national police chief after that, Ronald dela Rosa, now a senator, stand accused there of crimes against humanity for their war. Which raises the question: How might the ICC case be affected by such new and apparently earnest interest, as the congressional hearings tend to show, in getting at the truth about the war?

As early as 2021, the year before Duterte’s term ended, the Supreme Court had ruled that the ICC was justified in taking jurisdiction over the case. The Court meant that it didn’t matter that the Philippines had withdrawn from the arrangement that concedes jurisdiction to the ICC over crimes against humanity in signatory nations whose judicial systems are unable to deal with those crimes by international standards; the withdrawal came after the ICC had taken up the case.

But President Marcos does not want any ICC meddling, period. It seems he knows better than the Supreme Court — or knows the Supreme Court better.

To be sure, he has gotten away with defying its order for him to pay 200-plus-billion pesos in taxes. Also, his former election lawyer, now his appointed chairman of the Commission on Elections, has escaped being sanctioned for disobeying an order from the same Supreme Court to turn in certain records that should prove or disprove whether the vote, as claimed by doubters in their court suit, had been rigged for Marcos. But those favors are insignificant in the context of the ICC issue.

The ICC issue goes into the very core of the culture of patronage that has sustained the elitist and dynastic politics in this country. It shakes the happy status quo in which the Marcoses and their likes have flourished. That’s why not even Rodrigo Duterte, notwithstanding Marcos’s political break with his camp, should be turned over to the ICC. Actually, a trial could be staged for him under a Philippine law, passed in 2009, that precisely deals with “crimes against humanity,” so that the impression might be given that the ICC had become irrelevant. That arrangement should definitely make Duterte hopeful — recent history is on his side.

Marcos’s own mother, Imelda, a graft convict sentenced to six years, did not spend a day in jail. Joseph Estrada, convicted of plunder after being impeached as president, did go in but only stayed briefly, and comfortably, before being pardoned. Gloria Arroyo, the president who had pardoned him, herself a plunder indictee, was acquitted by a Supreme Court dominated by her own appointees. She now sits in Congress. Similarly, Estrada’s complicit son, Jinggoy, was acquitted, along with two fellow plunder indictees, and all three have resumed their enchanted political life: Jinggoy and old chum Bong Revilla are back in the senate, and Juan Ponce Enrile, chief crony of Ferdinand Marcos the dictator, is now chief counsel to his son, the president.

Surely, the justice system works — for the likes of them! But will the ICC be fooled? – Rappler.com